By Kirstyn McDermott

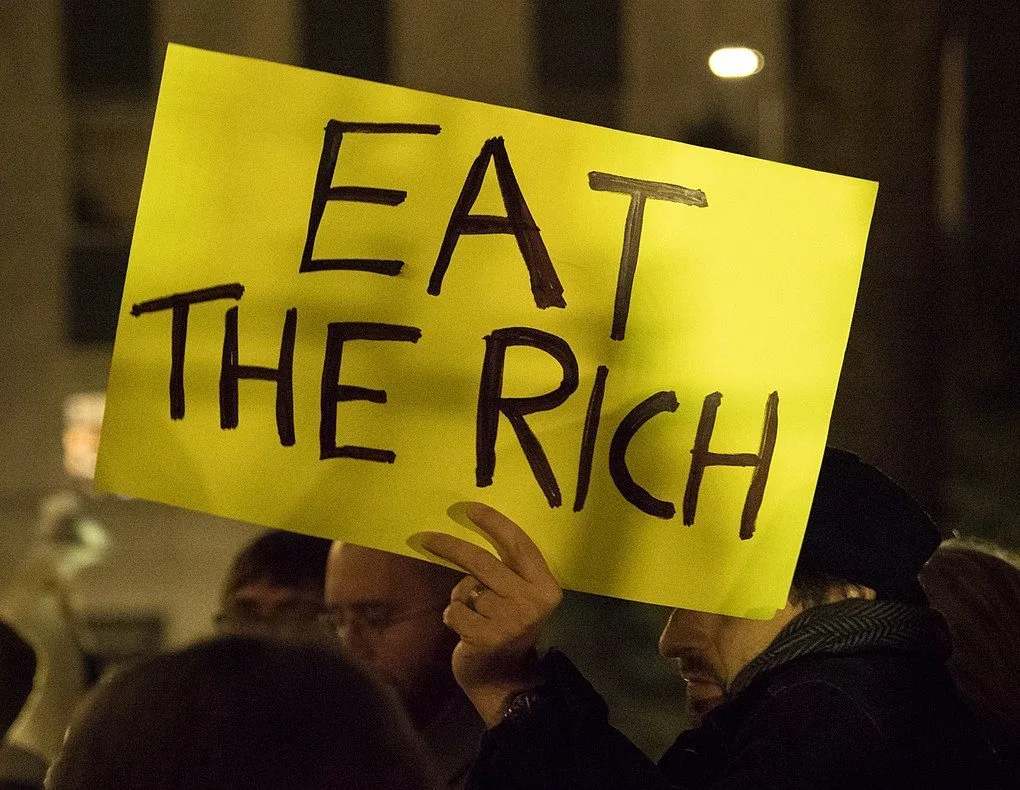

‘When the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich.’

– attributed to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1793

Horror on the screen has a deep and intimate knowledge of monstrosity and obscenity but films made for cinema have long needed to balance ratings and censorship boards with audience demand for the increasingly graphic, disturbing and downright gross, while television shows had to throw the concerns of advertisers into the mix. With the rise first of cable TV and then streaming giants, horror has enjoyed a small-screen renaissance with fewer constraints, and the technical advancement of both physical and digital effects this century has pushed boundaries, envelopes and, at times, viewer tolerances for gore and violence, regardless of whether we watch in a theatre, our living rooms or on tiny screens held in the palms of our hands.

No doubt due to its visual nature, screen horror eagerly embraced blood, guts and gore as much as it did shadows, screams and jump-scares, with ‘splatter films’ becoming an early, if largely cult, staple from the 1960s on. The first decade of the 21st century saw the emergence of the subgenre that came to be known as ‘torture porn’ after the moniker was coined in a review of the first Hostel (2005) movie. With its elaborate scenes of physical and sometimes sexual violence, lovingly rendered in hyper-realistic detail and often thrust upon the audience in extreme close-up framing, the subgenre is not for the squeamish. With the exception of the Saw franchise, soon to release its eleventh installment, torture porn has receded from the mainstream box office, but its bleeding-edge effects and aesthetics remain a strong influence within the wider horror genre and beyond.

The early years of this century also saw our first tentative forays into online life become supercharged by the advent of personal blogs, podcasts and social media networks, to the extent that Time magazine declared the 2006 Person of the Year to be . . . You. That is, us. The indispensable content creators of this brave new world. “It’s a story about community and collaboration on a scale never seen before,” wrote Lev Grossman for Time. “It’s about the many wresting power from the few and helping one another for nothing and how that will not only change the world, but also change the way the world changes.” In the cold, divisive light of 2025, such sentiments seem woefully naive. As we all know by now, if we’re not paying for the product, we are the product.

But social media, the 24-hour news cycle, and the Great and Terrible Interconnectivity of Now also means that we have all been there to witness the ostentatious grotesqueries of what we have hopefully—if not with some woeful naivety of our own—dubbed ‘late-stage capitalism’. Cost of living. Housing affordability. Wage decline. Privatisation. Financial crises. Climate change. Neo-fascism. Smug tech broligarchs. A-fucking-I. We witness and we post and we comment and we share and we create endless, endless memes. Because if we don’t laugh, we’ll cry. And if we start crying, we might never stop.

‘Poverty exists not because we cannot feed the poor, but because we can never satisfy the rich.’

– Anonymous, online, c.2020s

As of August 2025, the wealthiest individual in the world, Elon Musk, is worth $425 billion. The next three down the ladder, Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Ellison and Jeff Bezos, command around $250 billion each. Big numbers. We’re not good with big numbers. Our large primate brains evolved for purposes other than an ability to truly comprehend scale like the size of our universe, the age of our planet, the number of humans who have died in each protracted conflict and pandemic across the centuries, or the amount of coin in a billionaire’s bank account.

If you were given one dollar each and every second of your life, from the moment you drew your first breath until the moment your last slipped or sighed or rattled from your throat—a generous allowance of more than $31.5 million a year, to save you the math—it would take almost 8,000 years to scrabble your way to the bottom rung of the Super-Rich Top Five. For comparison, which is what our large primate brains are good at, the entire span of recorded human history covers only 5,000 years, beginning when ancient Sumerians first inscribed clay tablets with cuneiform. In case you were wondering, it would take 13,493 years to surpass Elon.

Of course, wealth is not the same as income but once you’re talking billions-with-a-b, the kind of income that generates renders money functionally meaningless. You can buy whatever you want, whoever you want. Eat anything you like, go anywhere that takes your fancy, do absolutely anything you wish with that one truly finite and nonrenewable resource: time. There won’t be enough of it to spend that amount of wealth, trust me.

‘Do you know what someone who doesn’t have any money has in common with someone with too much money to know what to do with? Living is no fun for either of them.’

– Oh Il-nam, Squid Game (2021)

The horror genre has always been quick to measure the emotional valence of the times. It harvests our fears and anxieties, from shared social concerns to the most intimate dread, and grinds them through the mills of metaphor and monster. Lately it has turned its attention to the super-rich, the ultra-wealthy elite, the one-percenters who hoard their wealth like bloated dragons ever greedy for more and more and yet still more, no matter the cost to the rest of us scrabbling below the economic tidelines or, indeed, to the whole world.

But this is horror. The genre is not content with Rousseauian exhortations to eat the rich, not when cannibalism was done to death in the twentieth century’s run of hillbilly horror spawned by films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977). When the shambling corpus of zombie movies has shown us so many ways a human can chow down on another human, eating human flesh has come to feel rather passé. Instead, this particular subgenre of horror is keen to demonstrate not only the monstrosity of the super-rich but to revel in the myriad and ever more elaborate methods by which they can meet their gruesome demises.

These narratives commonly frame killing the rich as direct acts of self-defence on the part of their victims, who are often from impoverished or disadvantaged backgrounds. Apparently bored with the easeful life that infinite wealth can provide, the super-rich turn exploitation into a game. In Blink Twice (2024), billionaire misogynists assault, rape and occasionally murder women on a private island, using a bespoke perfume to wipe the memories of any survivors and leaving their abusers with a unique trophy: a secret, intimate knowledge their still-adoring victims no longer possess. The Hunt (2020) laces high body count splatter with dark comedy, releasing a cohort of MAGA-meets-QAnon conspiracy nuts to be mercilessly tracked and slaughtered by an even more deplorable cadre of left wing ‘godless elites’. In Squid Game (2021-25), the poor, indebted or otherwise vulnerable ‘volunteer’ to take part in a series of challenges where failure results in execution, all orchestrated for the amusement of the uber-wealthy watching in comfort from afar.

Sometimes there is more at stake than simply fun and games. In the genre-breaking Get Out (2017), the bodies of young Black men and women are literally colonised by wealthy whites who desire their youth, health and other physical attributes—and who see no earthly reason why their generational wealth should not entitle them to it. Ready or Not (2019) drives a straighter if more delightfully gore-spattered line down the horror thoroughfare, pitching a newlywed bride against her husband’s old-money family who need to sacrifice her in order to honour a generations-old deal made with the devilish benefactor who secures their wealth—and their lives.

Because they act from self-defence, we have tacit permission to not only side with the victims and cheer on the almost inevitable Final Girl (or Final Boy) but to revel in the much-deserved killing of the rich. It doesn’t hurt that the wealthy are drawn as despicable, if not utterly evil, human beings. It’s perhaps also why Saltburn (2023) is a more uneasy viewing experience. While not core genre, the film sits horror-adjacent in its psychological manipulations and moments of genuine bodily cringe. On paper, the rich family is guiltless. They are thoughtless, cruel and manipulative, wielding wealth as a social weapon and thinking nothing of ruining the lives of others once they tire of playing with a particular toy—but surely they don’t deserve to die? Of course, we are not meant to side with the middle class protagonist either, a man who is playing his own game of manipulation and murder, casting himself as the “natural predator” of this particular strain of super-rich ‘spoiled dogs sleeping belly-up’.

‘Starvation, poverty, disease. You could solve all that and yet you don’t.’

– Verna, The Fall of the House of Usher (2023)

Kill the Rich as a subgenre tends to deal a twofold spectacle. There is the decadent, exclusive and impossibly expensive world of the super-rich—the food, the houses, the travel, the clothes, the parties and private islands—that the protagonists often desire and seek to enter. And there is the bloody Grand Guignol of gore, violence and death that this kind of horror promises its audience. The Netflix miniseries The Fall of the House of Usher (2023) delivers both in spades. A love letter to the works of Poe more than an adaptation, the series tracks the lives and gruesome deaths of the Usher family, orphaned siblings turned untouchable opioid oligarchs after they make a deal with the mysterious Verna—a powerful entity who often assumes the form of her anagrammatic namesake, the Raven. Interestingly, when promising the Ushers wealth, power and protection, Verna makes no demands on how they choose to live their lives. ‘I just want to see what you do,’ she tells them. She seems genuinely curious—and, by the end of the final episode, deeply disappointed.

It’s a capitalist nonsense to argue that a human being could do anything to earn the impossible wealth multi-billionaires possess, or to suggest that it could be accumulated without the exploitation of workers, never mind the pillaging of common natural resources and government coffers. While the Ushers commit no hands-on harm directly—not until the events of their final days, at least—their self-interested avarice is responsible for the deaths and addiction of countless millions. The very manner of their existence is an evil, regardless of the lack of actual blood on their hands. When the Usher offspring are given a choice before their own deaths—to end the rave, to rescue a different cat, to refuse the human test subject—each press on regardless. They still would have died, but their passing may have been as swift and peaceful as that of the truly blameless Lenore. The Raven is not without compassion or empathy, but she knows that karma is a weapon with the keenest edge.

‘You get the whole world,’ Verna tells Madeline and Roderick Usher in a bar back in 1980, ‘and the next generation can foot the bill.’ Which sounds very much like standard operating procedure for oligarchs. At the end of the first quarter of the twenty-first century, that bill has come due and Horror seems eager to ensure the right party pays it, gleefully adding the super-rich to the ranks of genre monsters we love to see—and see destroyed—on screen. Unlike vampires, zombies, aliens, cenobites or kaiju, however, this monster is all too real.